.

.

/

.

.

.

🔊 Please Turn Your Volume On !🔊

The History Of The Straits of Melaka

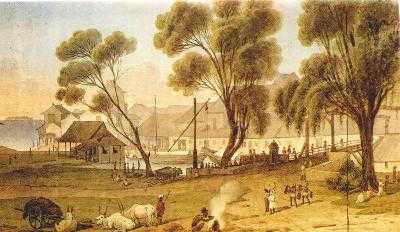

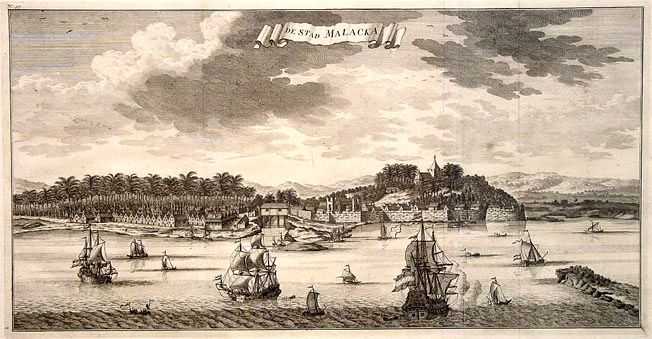

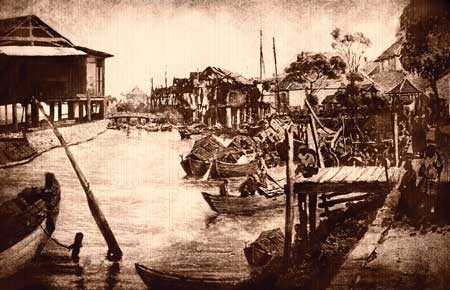

During the 15th to 17th century, one of the world’s most vital and popular trading ports was the Straits of Melaka, a narrow but powerful maritime corridor that connected China, India, the Middle East, and Europe through the Indian and Pacific Oceans (G. Vann, 2014). Its strategic location not only served as a gateway between East and West but also positioned it as a cornerstone of global trade. The cities of Melaka (Malacca) and Georgetown flourished along these waters, evolving into key hubs that shaped the course of world maritime history. Their harbors welcomed ships laden with spices, textiles, porcelain, and precious metals, while also facilitating the exchange of cultures, religions, and technologies.

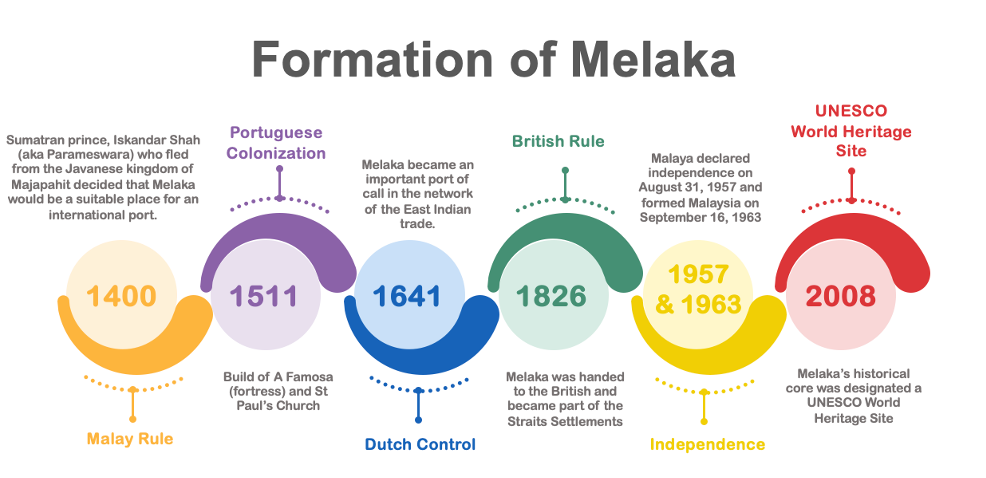

Melaka, in particular, rose to prominence as the capital of a powerful sultanate, attracting a cosmopolitan mix of traders from Arab, Indian, Chinese, and Malay origins. Its wealth and influence drew the attention of colonial powers, beginning with the Portuguese in 1511, followed by the Dutch in 1641, and eventually the British in the 19th century. Each left indelible marks on the region’s architecture, governance, and social fabric. Georgetown, established later by the British on Penang Island, complemented Melaka’s legacy by becoming a vibrant administrative and trade center during colonial rule. Both cities today reflect a richly layered cultural heritage, from colonial buildings and Peranakan traditions to multifaith religious sites and historic marketplaces.

Beyond trade, the straits also played a vital role in the spread of Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity, shaping the religious landscape of Southeast Asia. The enduring multiculturalism and maritime character of Melaka and Georgetown continue to reflect the strait’s significance. Now recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, these cities are living museums that symbolize centuries of global interaction, economic opportunity, and cultural synthesis, underscoring the historical and contemporary importance of the Straits of Melaka to Malaysia, Southeast Asia, and the wider world.

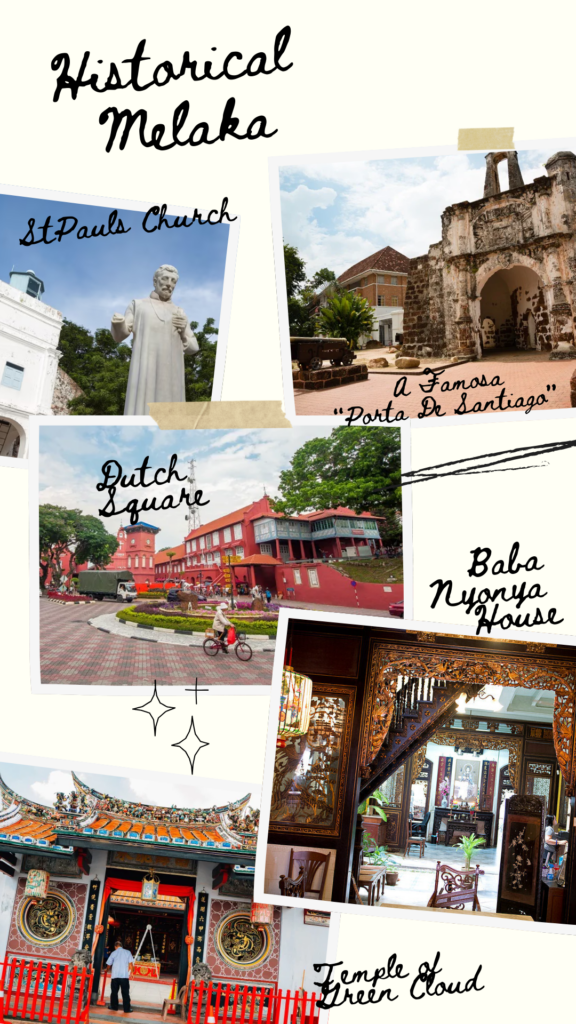

Melaka City, Melaka

💡Did you know?

The city got its name from a tree named Malacca

As the legend goes, while the Temasek ruler Parameswara was resting under a tree named Malacca, he witnessed a tiny mouse deer defeating his two hunting dogs and pushing them into the river. Startled by the might of the tiny creature, the ruler named Melaka after the tree he was seating beneath!

Melaka was the first great Maritime Kingdom in the Malay Archipelago

Ruled by the strongest Srivijaya Kingdom in the 15th century, there are records of many Chinese, Arab, and Indian traders lauding Malacca as the most influential port of the Southwest region in ancient times. A Portuguese trader who landed in Melaka in the 16th century said, “The city is of so much importance and profit. It seems to me it has no equal in the world!”

Malacca was once a fishing village occupied by the local Malays named Orang Lauts

Before the creation of any of the other Kingdoms into the Straits of Malacca, the people of Malacca lived peacefully under sloping rooftops of traditional Malay houses that used to hang over the water. They were mere fishermen pursuing their daily duties and influenced by none.

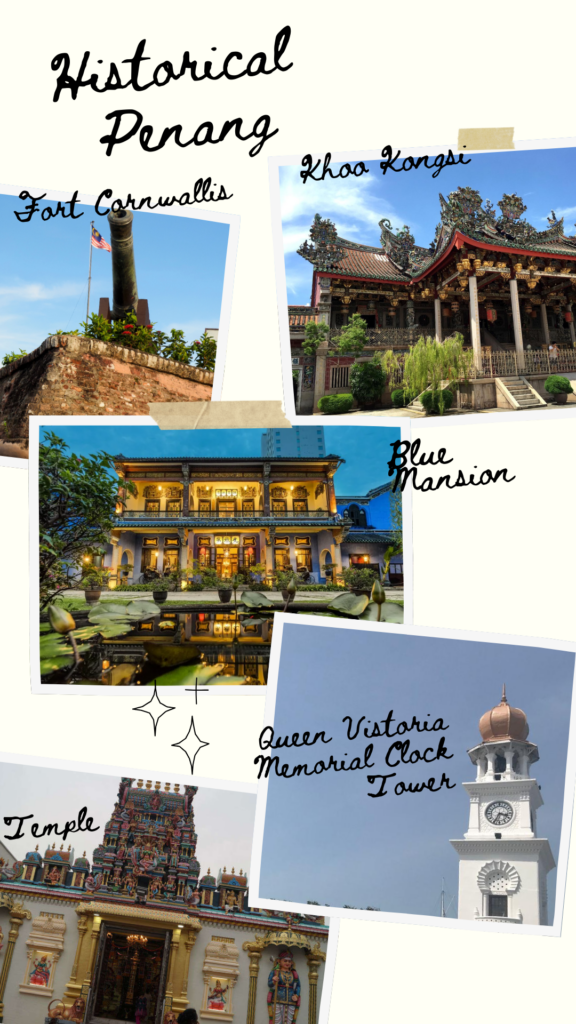

Georgetown, Penang

Georgetown in Penang Island, plays an equally important role in the success of the straits. It was often referred to as the “Pearl of The Orient” during the British Colonial Rule

💡Did you know?

Penang’s capital was named after a British Monarch

Penang’s colourful capital city, George Town, is named after King George III. The East India Company established the city in 1786 and it became the first British settlement in Southeast Asia soon after. It became part of the Straits Settlements, along with Singapore and Malacca, in 1868.

Penang is made up of two parts

Penang is the second smallest state in Malaysia. It comprises two halves : Penang Island and Seberang Perai.

It is home to the capital city, George Town. Seberang Perai (formerly Province Wellesley) sits on the Malay Peninsula. The state of Penang spreads across 1,048 square kilometers (404 square miles). Penang Island stretches across 750 square kilometres (285 square miles).

Penang’s name has interesting roots

The word Penang comes from the Malay word Pinang, which means betel nut tree. Originally, Penang was called Pulau Ka-satu or ‘First Island’. When the British settled here in 1786, they renamed it Prince of Wales Island to mark the birthday of the Prince of Wales. He later became George IV.

.

.

/

.

.

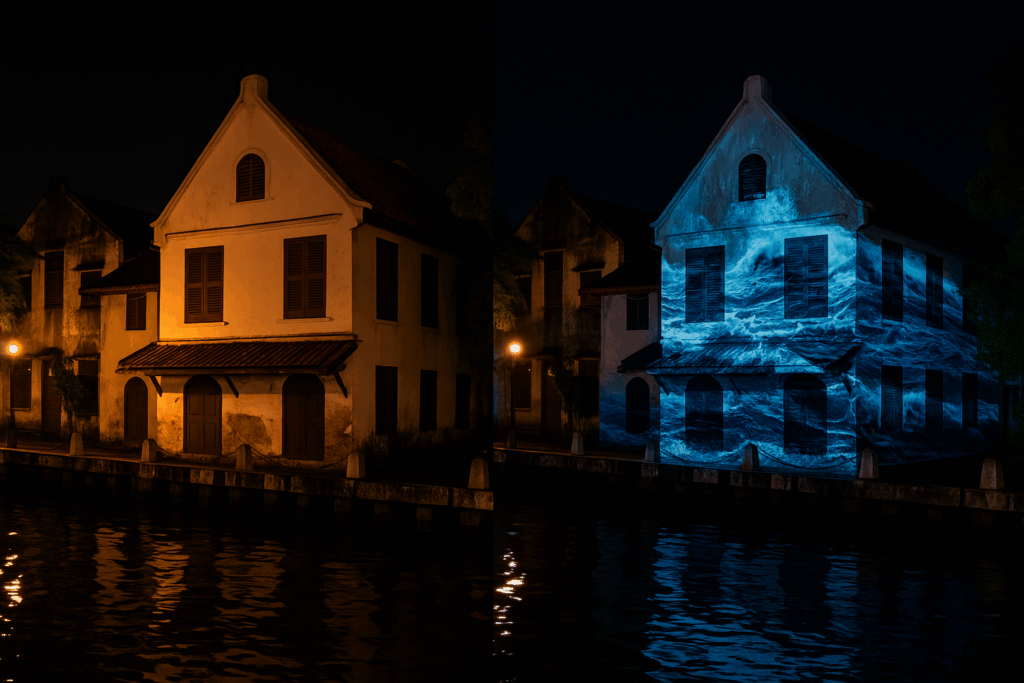

The Smart Interactive Projection Mapping System (SIPMS), is a digitally driven initiative geared towards educating, engaging, and empowering communities around the issue of heritage preservation and raising awareness on climate change. It addresses the urgent necessity to spread knowledge of the realities of the climate crisis and its effect on culturally rich yet vulnerable heritage zones in Malaysia which are Melaka and Georgetown, both UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

These two cities are situated along the Straits of Melaka, a historically significant maritime trade route. They embody centuries of cultural fusion where Malay, Chinese, Indian, Portuguese, Dutch, and British legacies are reflected in their architecture, traditions, and urban layout. However, the dual pressures of environmental degradation and urbanization challenge both tangible and intangible elements of these cities.

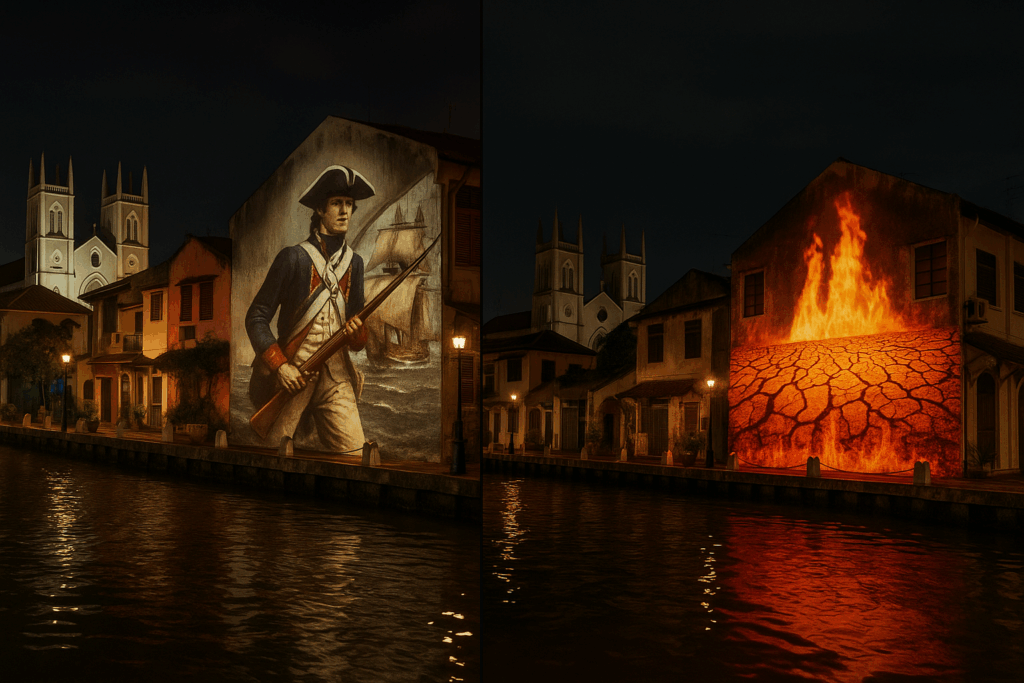

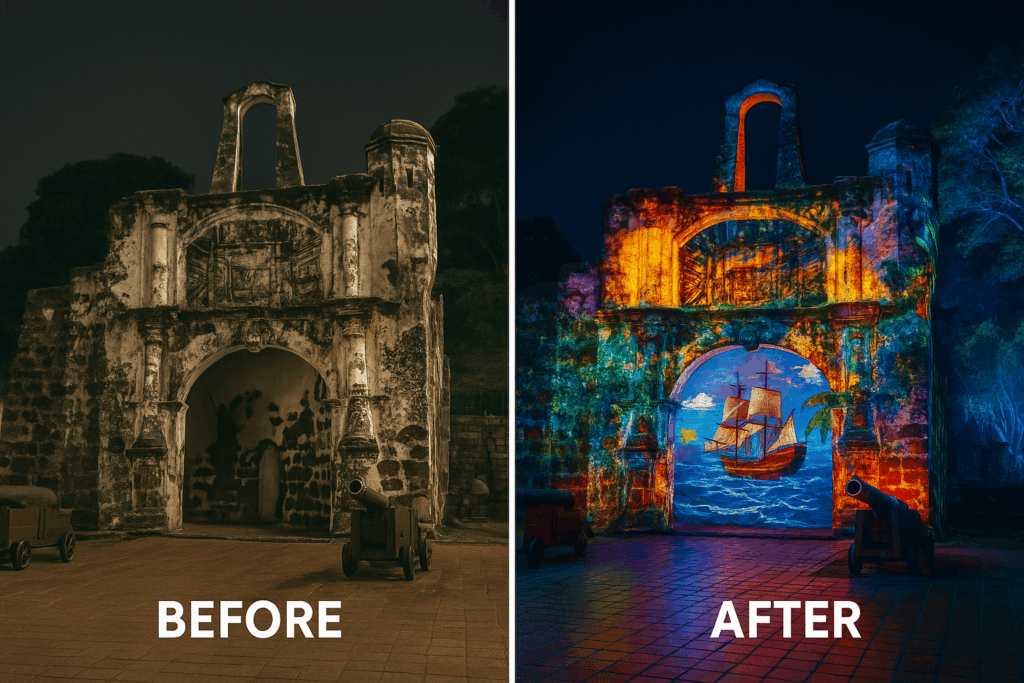

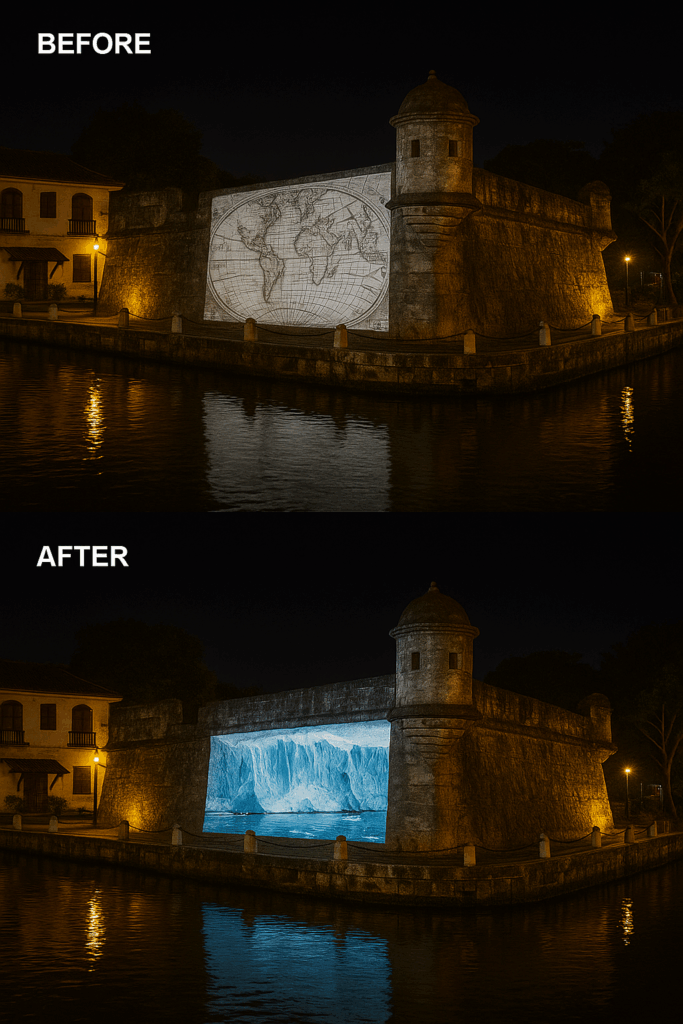

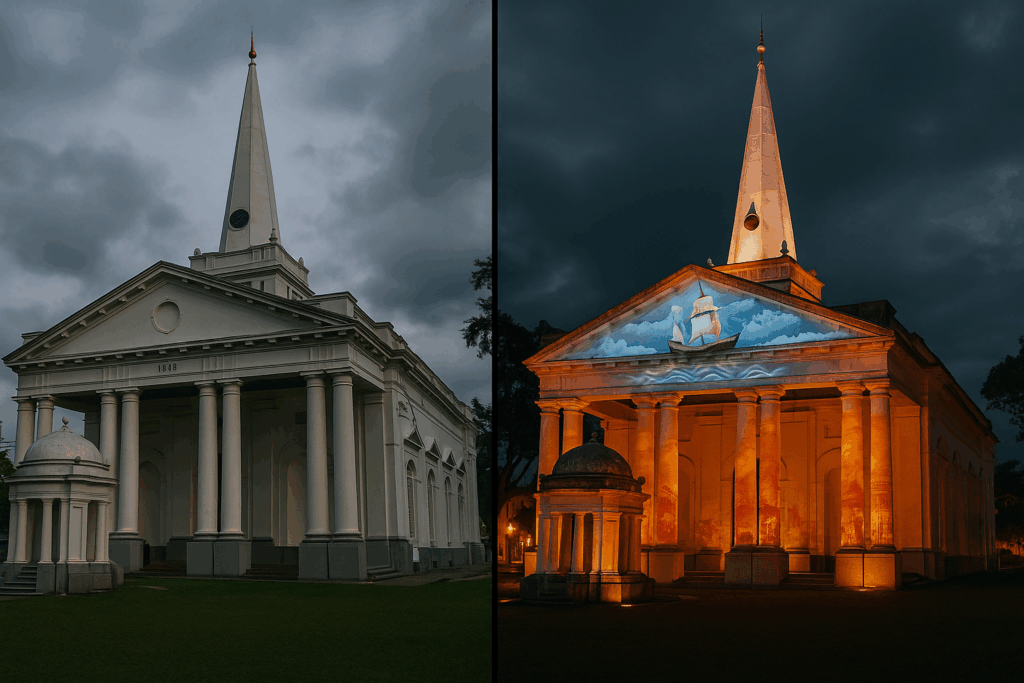

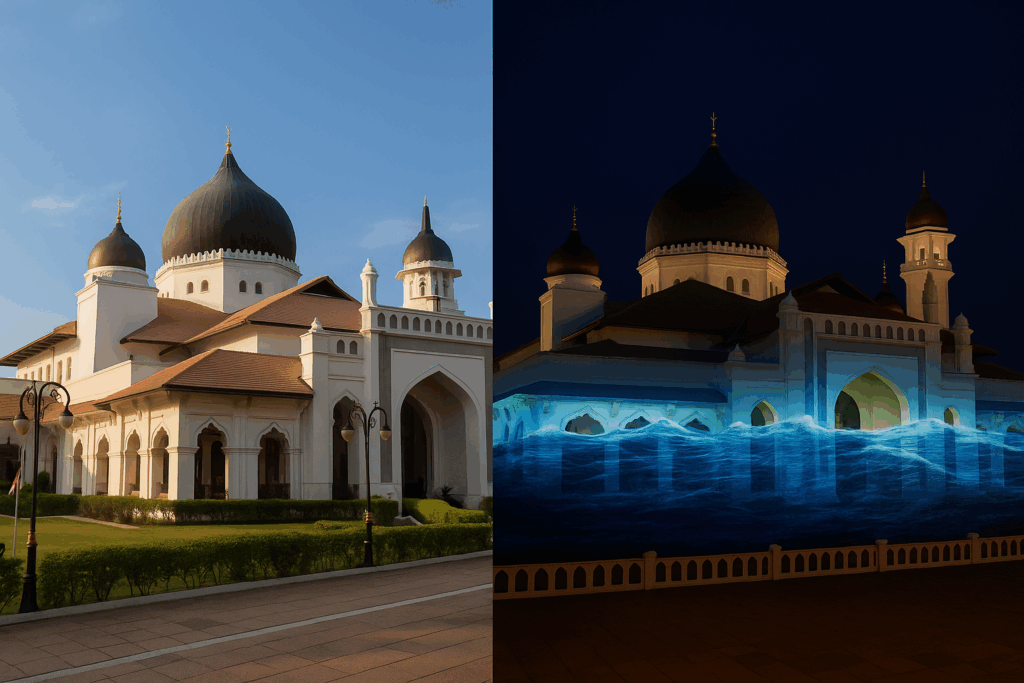

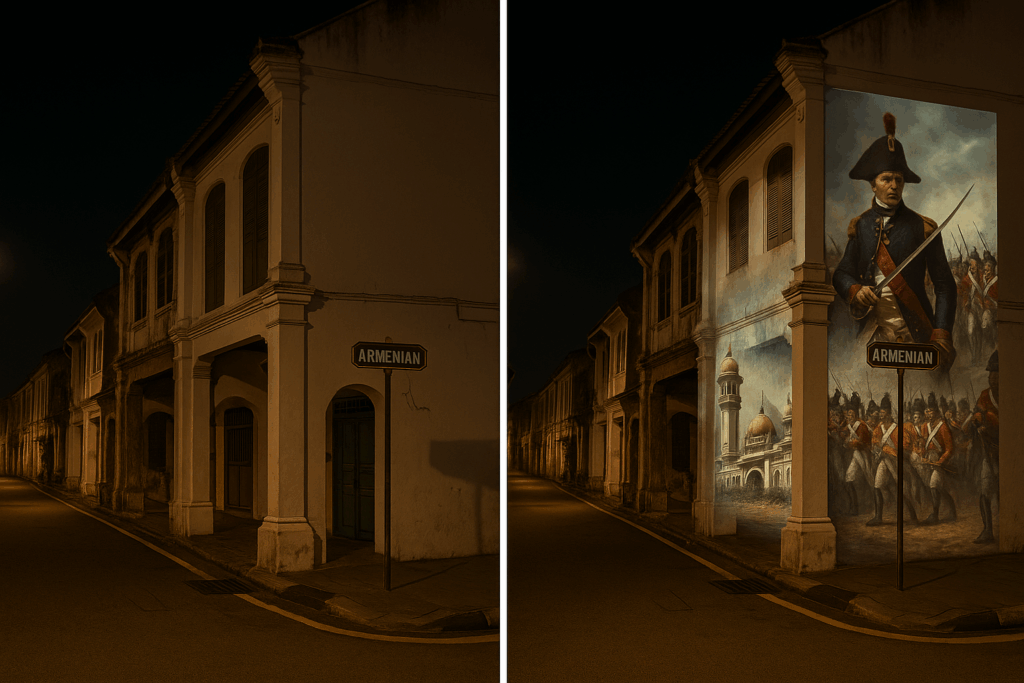

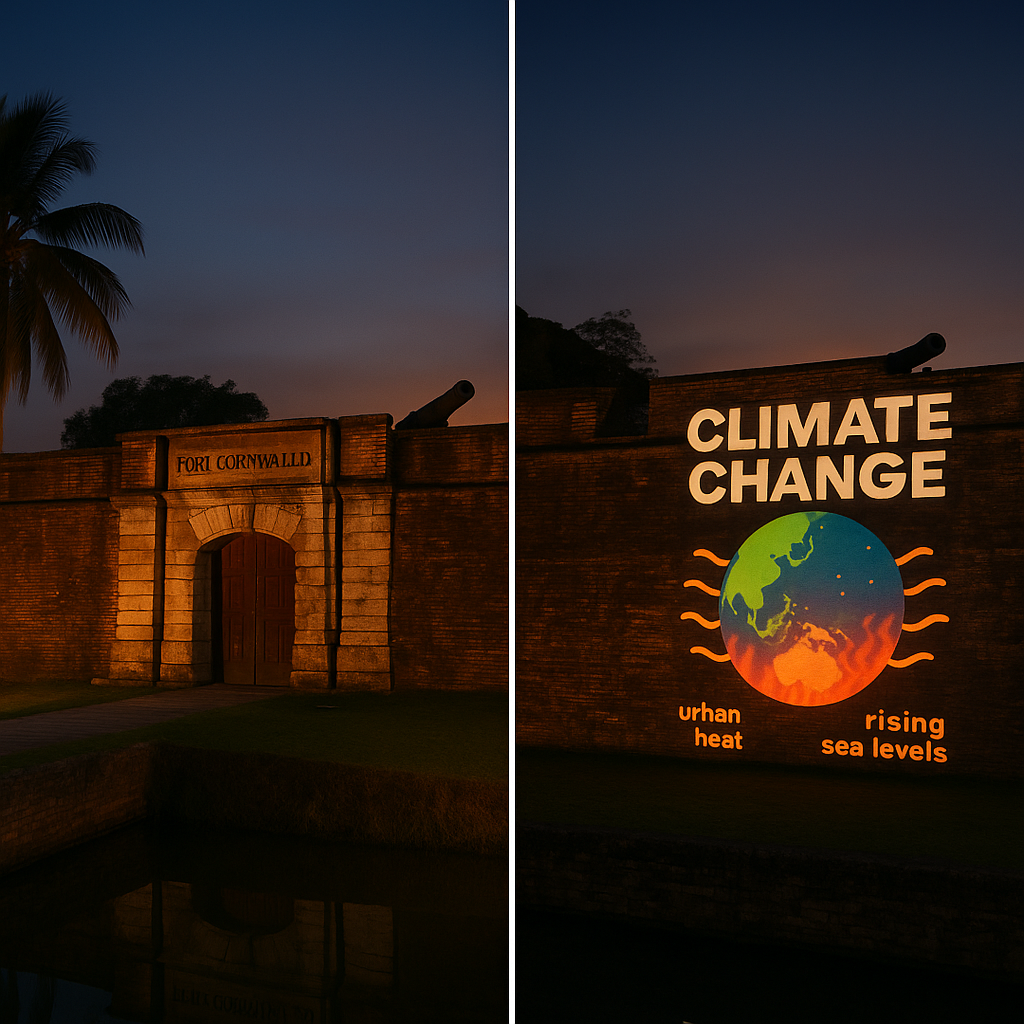

This SIPMS exhibit leverages projection mapping to display AI-generated and artist-curated stories onto significant heritage buildings, transforming public locations into immersive storytelling spaces. Through QR codes, users can also access exclusive content, additional historical data, interact with the mapping system, and even report on-site damage. Through this idea, the public will not only be able to experience the history of the place, but also envision future climate scenarios that is generated from predictive models. Overall, it promotes a low-impact, high-engagement experience that does not physically alter heritage sites.

The concept of SIPMS is inspired by similar global experiences such as Vivid Sydney, which uses light art to bring popular landmarks to life, Outernet London which tells stories through surround LED installations, and the Lindt Chocolate Museum, which uses QR-based interactions to deepen educational engagement. These exhibits have track records of increasing public interaction, encouraging learning, and boosting cultural tourism.

What is Projection Mapping

Existing Projection Mapping Experience

Explore The Projection Mapping Experience

Functionally, the exhibit is structured around a few main components: projection-mapped visuals, QR-linked mobile content, and music. At each site, visitors will encounter animated projections on historic buildings, these may include historical scenes, artistic interpretations, or visualised climate data. Nearby signage or physical stands will feature QR codes, which users can scan to access extended information, report issues and give feedback about the sites. QR code to web was chosen over a mobile app for a smoother process to access content and for higher accessibility. This design ensures the exhibit is maintainable, even across multiple locations.

Interaction is the main drawing factor of the exhibit’s appeal. Visitors can choose to engage passively by watching the light displays or actively by scanning QR codes that unlock more content. The QR will lead to options to leave feedback, explore timelines, locate more projection locations through an interactive map or even simulate future climate impacts on specific sites. The interactions are designed to be intuitive, accessible, and multilayered, offering different functionalities depending on user interest and background

Image Gallery

Interactive Map

QR Simulation

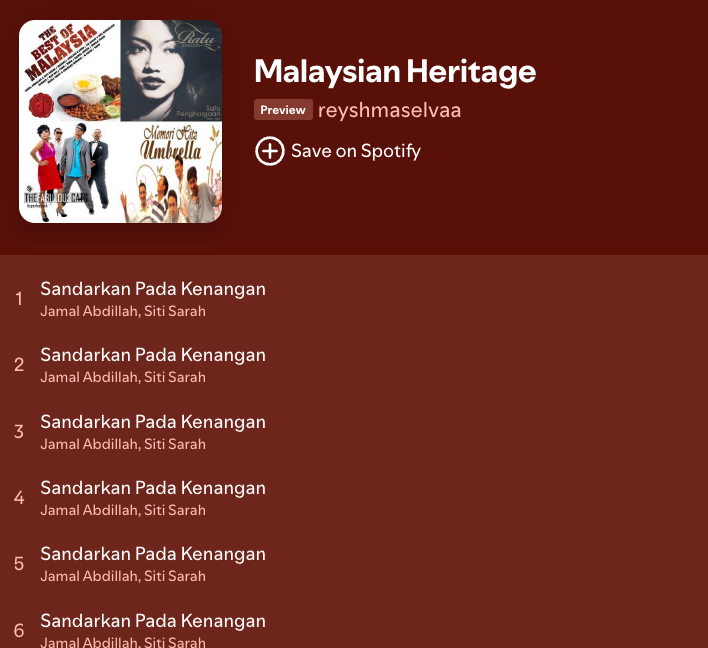

Music Playlist

Learn More

QR Simulation

Interaction is the main drawing factor of the exhibit’s appeal. Visitors can choose to scan QR codes around the city that unlock more content. The QR will lead to options to leave feedback, explore timelines, or even simulate future climate impacts on specific sites. The interactions are designed to be intuitive, accessible, and multilayered, offering different functionalities depending on user interest and background. For example, tourists may want quick facts, while students could explore interactive climate models. These interaction pathways enable the concept of participatory heritage and interaction, where audiences contribute to conservation efforts by submitting feedback and reporting issues. By inviting the public to and adjust climate sliders or digital timelines, it is also empowering them to visualize complex environmental futures in relatable ways (Simon, 2010)

Mockup of QR Code Interaction for sites in Melaka

Mockup of QR Code Interaction for sites in Penang

Interactive Map

The Interactive Map Feature from the QR Code, can be seen below. The users of the system will be able to locate all the possible areas were projection mapping installations have been placed so that they are free to explore different sites

Image Gallery

Projection Mapping Mockup in Melaka

Projection Mapping Mockup in Penang

Music To Accompany The Projection Mapping

Environmental Threats

Rising Sea Levels and Flooding

Among the most pressing environmental threats facing Melaka and Georgetown’s heritage sites are rising sea levels and flooding (Masterson, Hall, & North, 2025). Both cities are situated on the Straits of Melaka coast and are thus exposed to tidal surges, coastal erosion, and flooding (Ehsan, Abdul Maulud, Begum, & Mia, 2022). Places like Melaka River and Weld Quay in George Town are low-lying and near water bodies, where minor rises in sea level can result in massive flooding (Pandya-Wood & Azhari, 2024). Not only do these floods destroy infrastructure, but also affects historic waterfront structures many of which are centuries old and were constructed without flood-resistant and drainage infrastructure.

Rising Temperature and Humidity

Rising temperatures and high humidity, also cause the deterioration of heritage buildings. In the tropical Malaysian climate, direct sunlight, rain, and changing humidity create conditions that build the development of mold and algae (Walder, 2023). These degrade the stonework, woodwork, paint, and even metal, weakening structural integrity over the long term (Mitchell-Rose, 2019). Colonial-era buildings and pre-war shop lots are especially vulnerable, and unless measures are taken, many of them will face serious damages.

Fast Paced Urbanization

There is also the factor of fast-paced urbanization which poses a social and cultural threat to these heritage cities. Expansion of commercial hubs, high-density constructions, and infrastructure projects most often take their toll on continuity in architecture (Clough, 2023). With the commercialization of historic neighbourhoods also comes displacement of its residents, increased rents, and pressure to modernize, resulting in the erosion of local identity and traditions (Smith, 2023). Over-commercialization also capitalises heritage, losing its authenticity

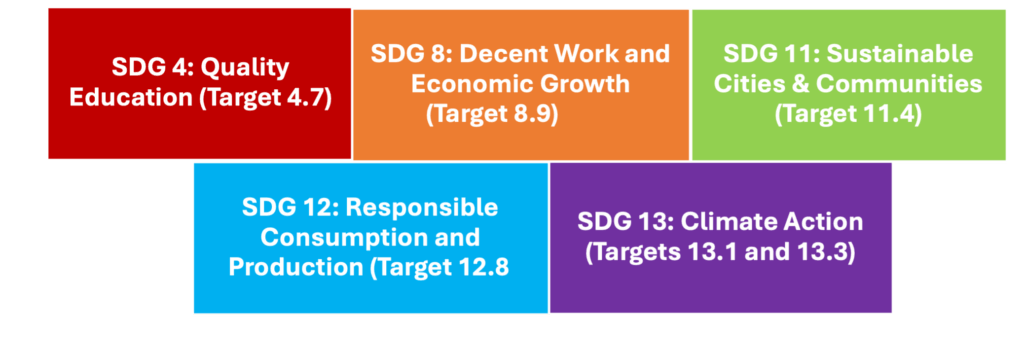

Sustainable Development Goals

The Smart Interactive Projection Mapping Exhibit directly supports several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), promoting sustainable cultural engagement, climate action, education, and community development.

SDG 4: Quality Education (Target 4.7)

The exhibit is designed not just for visual engagement, but as a tool for learning. Through historical narratives and climate awareness the project offers a platform for education to diverse audiences. It supports SDG 4.7, which supports education that promotes sustainable development and cultural diversity.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth (Target 8.9)

The project offers new opportunities for local employment, particularly for artists, technicians, cultural researchers, and tourism professionals. This supports SDG 8.9, which promotes sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities (Target 11.4)

The project serves as a non-invasive means of cultural preservation, protecting heritage buildings while celebrating its stories. By using digitally projected formats, the project minimizes the need for interior renovations or negative repercussions from heavy tourist foot traffic, such as structural degradation. This aligns directly with SDG 11.4 by providing a tech-driven, participatory approach to safeguarding urban heritage environments. .

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production (Target 12.8)

Unlike traditional exhibits that require physical materials, the Smart Interactive Projection Mapping System is designed to be energy-efficient and mobile. This aligns with SDG 12.8, which seeks to ensure people have the relevant information to support sustainable lifestyles. By engaging the public with a conscious, low-footprint design, the exhibit sets an example for future cultural programming in heritage cities.

SDG 13: Climate Action (Targets 13.1 and 13.3)

The projections visualises the past, present, and possible future of heritage sites in Melaka and Georgetown, showing users how rising sea levels, temperature fluctuations, and extreme weather affect culturally significant buildings. By communicating these realities through visual projections, the project addresses SDG 13.1 which addresses climate resilience and adaptive capacity as well as SDG 13.3 that covers climate education and awareness.

References :

Amir, S., Osman, M. M., Bachok, S., & Ibrahim, M. (2016). Local Economic Benefit in Shopping and Transportation: A study on Tourists’ Expenditure in Melaka, Malaysia. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 222, 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.186

An interactive chocolate tour for chocolate lovers. (2025). Retrieved from Lindt Home of Chocolate website: https://www.lindt-home-of-chocolate.com/en/chocolate-museum-tour/

Barghi, R., Zakaria, Z., Hamzah, A., & Hashim, N. H. (2017). Heritage education in the Primary School Standard Curriculum of Malaysia. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.012

Brunero, D. (2021). Southeast Asia’s Colonial Port Cities in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.554

Bujang, D. (n.d.). Jabatan Warisan Negara. Retrieved from JWN 2020 website: https://www.heritage.gov.my

Chen, K. (2023). Features of Portuguese colonial architecture in South Asia in the period from XVI to XVIII centuries. Culture and Art, (12), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.7256/2454-0625.2023.12.41049

Chung, Y. Y., & Tan, T. (2021, October 24). The cultural and historical significance of Old Melaka. Retrieved from The Edge Malaysia website: https://theedgemalaysia.com/article/cultural-and-historical-significance-old-melaka

Ganesan, V., Noor, S. Md., & Jaafar, M. (2014). Communication Factors Contributing to Mindfulness: A Study of Melaka World Heritage Site Visitors. Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n3p49

Ghani, J. A. (2024, December 28). Budget 2025 sets the course for a digital future. Retrieved from Free Malaysia Today | FMT website: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/opinion/2024/12/28/budget-2025-sets-the-course-for-a-digital-future/

Inspired by Vivid: Immersive Installations from Global Festivals. (2024). Retrieved from Futurelabsco.com website: https://www.futurelabsco.com/news/inspired-by-vivid-immersive-installations-from-global-festivals

Khor, N. (2006). ECONOMIC CHANGE AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE STRAITS CHINESE IN NINETEENTHCENTURY PENANG. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 79(2 (291)), 59–83. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/41493673

Malaysia Heritage | Tourism Malaysia. (2025, February 11). Retrieved from heritasian.com website: https://heritasian.com/malaysia-heritage/

MDEC. (2019). MDEC. Retrieved from MDEC website: https://mdec.my/

Mes, M. (2024, December 21). The Dark Side Of Industrial Revolution: Environmental Destruction – Massive Earth Foundation. Retrieved from Massive Earth Foundation website: https://massivefoundation.org/opinion/dark-side-of-industrial-revolution/

Pitakdumrongkit, K. (2023, October 5). Geoeconomic Crossroads: the Strait of Malacca’s Impact on Regional Trade. Retrieved from The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) website: https://www.nbr.org/publication/geoeconomic-crossroads-the-strait-of-malaccas-impact-on-regional-trade/

Portal Rasmi Kementerian Pelancongan, Seni dan Budaya Malaysia. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.motac.gov.my website: https://www.motac.gov.my/

Portal Rasmi Kerajaan Negeri Pulau Pinang. (n.d.). Retrieved from Portal Rasmi Kerajaan Negeri Pulau Pinang website: https://www.penang.gov.my/index.php?lang=ms

Portal Rasmi Melaka. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.melaka.gov.my website: https://www.melaka.gov.my/

Ragheb, A., Aly, R., & Ahmed, G. (2021). Toward sustainable urban development of historical cities: Case study of Fouh City, Egypt. Ain Shams Engineering Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2021.06.006

Richardson, J. (2024, March 7). Transformative Experience Through Storytelling. Retrieved from MuseumNext website: https://www.museumnext.com/article/transformative-experience-through-storytelling/

Rusli, M. H. B. M., Suherman, A. M., Yuliantiningsih, A., Wismaningsih, W., & Indriati, N. (2021). The Straits of Malacca and Singapore: Maritime Conduits of Global Importance. Research in World Economy, 12(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.5430/rwe.v12n2p123

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (2008). Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca. Retrieved from UNESCO World Heritage Centre website: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1223/

United Nations SDG. (2015). The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from United Nations website: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

UNWTO. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19 – unprecedented economic impacts. Retrieved from UNWTO website: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-and-covid-19-unprecedented-economic-impacts

Wahab, A., Rusli, N., Irwan Mohammad Ali, & Md Yusof Hamid. (2023). Building Defects in the Coastal Environment of Malaysia: An Investigation of the Main Agents and Contributing Factors. International Journal of Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v13-i4/16773

Williams, T. (2010). Melaka and World Heritage Status. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 12(3), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1179/175355210×12838583775301

Wood, P. (2024, December 12). Sea level rise a clear threat to Malaysia. Retrieved from Eco-Business website: https://www.eco-business.com/opinion/sea-level-rise-a-clear-threat-to-malaysia/

Barghi, R., Zakaria, Z., Hamzah, A., & Hashim, N. H. (2017). Heritage education in the Primary School Standard Curriculum of Malaysia. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.012

Big Picture & CT Light Up the UN HQ with an Impressive Projection Mapping Project. (2024, November 12). Retrieved April 14, 2025, from Creative Technology website: https://ct-group.com/me/projects/un-headquarters-climate-change-projection-mapping/

Brunero, D. (2021). Southeast Asia’s Colonial Port Cities in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.554

Clough, H. (2023, October 20). Implementing modular integrated construction in high-rise high-density cities. Retrieved from Planning, Building & Construction Today website: https://www.pbctoday.co.uk/news/mmc-news/implementing-modular-integrated-construction-in-high-rise-high-density-cities/133685/

Destination NSW . (2019, May 8). Vivid Sydney | Light, Music & Ideas Festival. Retrieved from Vivid Sydney website: https://www.vividsydney.com

Ehsan, S., Abdul Maulud, K. N., Begum, R. A., & Mia, M. S. (2022). Assessing household perception, autonomous adaptation and economic value of adaptation benefits: Evidence from West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Advances in Climate Change Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2022.06.002

Gaitatzes, A., Christopoulos, D., & Roussou, M. (2001). Reviving the past. Proceedings of the 2001 Conference on Virtual Reality, Archeology, and Cultural Heritage – VAST ’01. https://doi.org/10.1145/584993.585011

Giannini, T., & Bowen, J. P. (2019). Museums and Digital Culture. In Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97457-6

Gregory, E. (2024, January 8). Immersive 360° film at Outernet London shows astonishing life cycle of jellyfish. Retrieved from The Standard website: https://www.standard.co.uk/esrewards/exhibitions/jellyfish-film-forsaken-outernet-london-tottenham-court-b1130872.html

Hawkey, R. (2004). Learning with Digital Technologies in Museums, Science Centres and Galleries REPORT 9: FUTURELAB SERIES. Retrieved from https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/eecph0ty/futl70.pdf

Historic Environment. (2014, April 9). Retrieved from GOV.UK website: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/conserving-and-enhancing-the-historic-environment

IPCC. (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. IPCC, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.59327/ipcc/ar6-9789291691647.001

Kunimoto, C. (2022, July 12). 10 ways projection can improve your sustainability. Retrieved from Blooloop website: https://blooloop.com/technology/opinion/projector-sustainability/

Masterson, V., Hall, S., & North, M. (2025, March 25). Sea level rise: Everything you need to know. Retrieved from World Economic Forum website: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/03/rising-sea-levels-global-threat/

Major accolade for Vivid Sydney at Australian Event Awards. (2024, October 24). Retrieved from Destinationnsw.com.au website: https://www.destinationnsw.com.au/newsroom/major-accolade-for-vivid-sydney-at-australian-event-awards

Miedema, M., Aasman, S., Beaulieu, A., & Sauer, S. (2025). An ecologically just future for personal digital heritage: three guiding statements. Archival Science, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-025-09481-1

Mitchell-Rose, C. (2019). Paint, Wood and Weather. Retrieved from www.buildingconservation.com website: https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/paintwoodweather/paintwoodweather.htm

MOTAC. (2023). Malaysia Tourism Key Performance Indicators. In MOTAC. Retrieved from https://data.tourism.gov.my/frontend/pdf/Malaysia-Tourism-Key-Performance-Indicators-2023.pdf

Outernet. (2024, January 8). FORSAKEN Celebrates The Beauty of the Immortal Jellyfish and Sounds a Sombre Warning. Retrieved from www.outernet.com website: https://www.outernet.com/news/forsaken-celebrates-the-beauty-of-the-immortal-jellyfish-and-sounds-a-sombre-warning

Pandya-Wood, R., & Azhari, A. (2024). Sea Level Rise Is a Clear Threat to Malaysia. Retrieved from Thediplomat.com website: https://thediplomat.com/2024/11/sea-level-rise-is-a-clear-threat-to-malaysia/

Podara, A., Giomelakis, D., Nicolaou, C., Matsiola, M., & Kotsakis, R. (2021). Digital Storytelling in Cultural Heritage: Audience Engagement in the Interactive Documentary New Life. Sustainability, 13(3), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031193

Pitakdumrongkit, K. (2023, October 5). Geoeconomic Crossroads: the Strait of Malacca’s Impact on Regional Trade. Retrieved from The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) website: https://www.nbr.org/publication/geoeconomic-crossroads-the-strait-of-malaccas-impact-on-regional-trade/

Protection and Management of World Heritage Sites (2024, December 20). Retrieved from Historicengland.org.uk website: https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/planning/world-heritage/protection-management/

Rusli, M. H. B. M., Suherman, A. M., Yuliantiningsih, A., Wismaningsih, W., & Indriati, N. (2021). The Straits of Malacca and Singapore: Maritime Conduits of Global Importance. Research in World Economy, 12(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.5430/rwe.v12n2p123

Simon, N. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Retrieved from Google Books website: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=qun060HUcOcC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=Simon

Selva, R. (2025) PRACTICAL 2: DIGITAL PRESERVATION AND PROMOTION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE. IS5110: Digital Heritage and Preservation. The University of St Andrews. Unpublished assignment.

Smith, R. (2023, August 8). Gentrification Pros and Cons: A Double-Edged Sword. Retrieved from Robert F. Smith website: https://robertsmith.com/blog/gentrification-pros-and-cons/

Stephenson, L. (2023). Cultural Heritage: Its Significance and Preserving. Anthropology, 11(4), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.35248/2332-0915.23.11.321

TRACK | IPBES Secretariat. (2024). Retrieved April 12, 2025, from IPBES Secretariat website: https://www.ipbes.net/impact/75287

Using Digital Technologies to Innovate in Heritage Research, Policy and Practice. (2021). Retrieved from Starts.eu website: https://starts.eu/article/detail/report-digital-technologies-heritage-research-policy-practice-unesco/

Walder, N. (2023, May 25). Subtropical and tropical zones and their influence on the indoor climate. Retrieved from Stadler Form website: https://www.stadlerform.com/en-ch/rooms/public-space-air-quality/subtropical-and-tropical-zones-and-their-influence-on-the-indoor-climate