BRINGING THE PAST INTO THE FUTURE

The Cave of Altamira, located in the Spanish region of Cantabria, contains some of the oldest wall art known to man, with some of the paintings dating as far back as the Upper Palaeolithic period over 36,000 years ago. The art includes a multitude of charcoal drawings and polychrome paintings depicting handprints, claviform symbols, masks and, most prevalently, various animals including deer, horses and bison. Approximately 13,000 years ago a rock fall sealed the cave’s entrance, preserving the art inside until the day a nearby tree fell and disturbed the fallen rocks. Discovered in 1868, the cave was investigated further by a local nobleman that, alongside the art, unearthed a number of animal bones and stone tools. Due to its isolation from external climactic influences, it is some of the best preserved prehistoric art that has ever been discovered.

PREHISTORIC ALTAMIRA

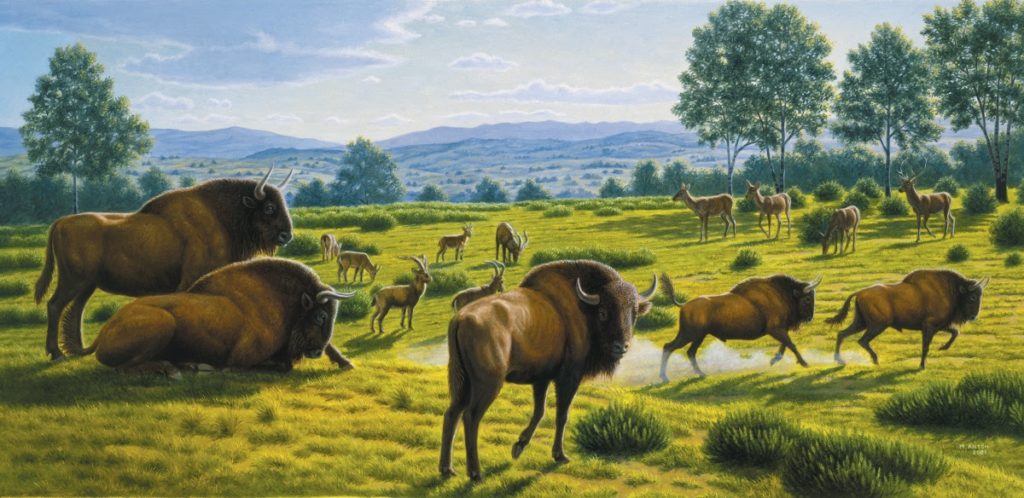

During around 40,000 BC, the first humans arrived on the Iberian Peninsula, living alongside Neanderthals for over 12,000 years. During this time, Altamira, located near the northern coast of Spain, was a mild, wet climate following the Last Glacial Maximum. The area comprised of open spaces and meadows filled with vegetation, and while pine, oak and birch forests were scarce, they were still present. Homo sapiens, throughout this Upper Palaeolithic period, developed various cultures that were responsible for the shaping of different stone and bone tools such as Solutrean points, scrapers, burins, spears, harpoons, and pendants, many of which have been found by archeologists within the cave. These same tools would have been used to hunt the local wildlife, which primarily comprised of bison, horses, oxen, deer, and mountain goats.

The Cave of Altamira acted as a shelter from both the weather and wildlife for humans living during this period. The cave entrance acted as an ideal spot for campfires, where oncoming danger could be easily spotted, animal corpses could be flayed and cooked, and people could carry out their daily chores and socialise with one another. The cave itself, approximately 1000m long and

consisting of a series of passages and chambers, was ideal for sleeping, tending to the young, and painting. With the cave ceiling ranging between 2 and 6 meters in height, the lower portions were in perfect reaching distance for the creation of art within the cave, especially with the assistance of the protruding rocks from the ground. In a time before literature, paintings acted as a form of true expression, immortalising a fragment of a person’s day-to-day lifestlye, their beliefs, their fears, and their ecounters with the world around them. It is a common misconception that the Altamiran cave art was created over no more than a few generations. Owing to uranium-thorium dating, researchers have found that, in fact, the paintings within these caverns span over a period of up to 20,000 years. The oldest wall art within the cave dates as far back as 36,000 years ago and were made with charcoal and hematite, with no use of colour. In contrast, the more recent paintings comprise primarily of ochre and iron oxides, bringing shades or red and yellow to the wall art. The more recent paintings were also larger in size, with one in particular depicting a stag almost 2.5 meters in length. What makes the art all the more impressive however, is not just its very existence and preservation, but the manner in which it was made.

The majority of the coloured paintings within the Cave of Altamira were first engraved into the wall using flint tools in order to sketch the outline. Then, this outline was drawn with charcoal or hematite before being filled in with various colours. The placement of these paintings is especially fascinating, as the bumps and cracks along the walls were intentionally used to give volume and dimension to the animals drawn, resulting in the artwork protruding out to those looking at them from above. These techniques not only required a degree of precision and skill, but also creative thinking. While a variety of incredible prehistoric discoveries have been made, such as ivory figurines, wooden boats, and stone tools, few things truly bridge the gap between our world today and that of the old world quite like art, as it gives us a glimpse into not only the world during that period, but the minds of the people inhabiting it. It is of little surprise that the cave has been deemed as a masterpiece of creative genius, and as humanity’s earliest accomplished art.

THE RECENT DECADES

Within the last 50 years, the Cave of Altamira has seen incredible success in regard to tourism. Throughout the 1970s, Altamira attracted more than 150,000 visitors per year, reaching as high as 174,000 visitors in 1973. This spike saw huge benefits to the local community and economy, with new hotels, restaurants, and small businesses opening up throughout the area. However, during the late 70s, scientists found that the paintings were experiencing deterioration due to the body heat and CO2 expelled by visitors within the cave. For this reason, the cave was closed off to tourists in 1977.

Just a few years later, in 1982, the cave was reopened but with a limit of 11,300 visitors each year, which subsequently resulted in waiting lists of as long as three years! However, the cave was once again closed in 2002 due to the appearence of green mould on some of the paintings as a result of body heat, artificial light, and humidity fluctuations produced by its visitors.

The following is an image gallery in the form of an interactive document, depicting why the Altamiran cave art is as risk:

https://www.flipsnack.com/mcim1/why-is-the-cave-of-altamira-at-risk.html

In 2020, the Museum of Altamira released an animated virtual experience providing a look into the cave during the Upper Palaeolithic period, depicting how early humans would have gone about inhabiting it and utilising its narutal structure for shelter and painting. In order to create this animated experience, multiple 3D laser scans were taken so to digitally construct the cave.

Years before the release of the animated tour, researchers at the museum began to notice that the pigment particles on the paintings were rapidly deteriorating. In 2000, this encouraged the beginnings of a gargantuan project to create a replica of the cave. To do this, the company Tragacanto from Madrid was hired. Every detail of the cave was captured through a 3D scanner, a similar process to that carried out when creating the animated tour years later. Using this scanner, over 6 million geometrical data points were acquired for the roof sections alone. After eight months and a surface area of 2600 square meters, the scanning stage was complete. Based on the model generated from these data points, foam blocks were cut into different segments of the cave. After applying wax and silicon molds of the surface of the cave, the final silicon wall sections were added. The artists and and researchers then went about reconstructing the actual paintings, which was done using a similar technique to that used by the prehistoric humans that resided there thousands of years ago. This technique involved taking mineral pigments diluted in water and applying it to the artificial limestone surface of the replica, which possessed the same absorbency as the stone within the original cave. The paintings were also created at the same temperature as within the cave in order to make it as authentic as possible.

THE FUTURE OF ALTAMIRA: VIRTUAL REALITY EXPERIENCE

While the animated tour and cave replica created by the Museum of Altamira are incredibly impressive, and act as great alternatives to seeing the original cave itself, they still possess some flaws. The replica, while still atmospheric, is noticably artificial with signs that it was made in recent years, not to mention the fact that it is located in Altamira. It is reasonable to say that a lot less people, at least on an international level, would not be compelled to travel such a far distance to observe a replica. The animated tour video, while immersive, is limited in that it only shows a fraction of the cave, exploring merely a few select paintings. Owing to the marvel of modern technology however, there is now the opportunity for a new alternative. A high definition, virtual reality experience of the Cave of Altamira.

The VR industry has grown immensely over the last decade, and is anticipated to grow fourfold within the next decade. While many believe the technology to be limited to gaming, it is prominent within various industries, including sports, the military, education, and even mental health treatment.

Using VR technology, a virtual tour can be created allowing the user to wander the Cave of Altamira at any point in the it’s history, travelling as far back as when the first painting was made, all the way to the present day. Utilising hyper-realistic graphics, the VR experience would add an element of immersion unlike anything seen before, allowing the user to navigate the cave openly and interact with the surrounding area. This could include watching a prehistoric human painting a bison, observing tools being crafted, watching animals take shelter, picking up and throwing rocks, and even looking out from the cave entrance upon the world as it would have been during the Paleolithic period. Through the user’s headphones, the sounds of the crackling campfire, ambient weather, and distant sounds of prehistoric animals, would add a layer of immersion that would truly complete the experience.

The graphics used in virtual reality today have come a long way, and are especially prevolent in recent video game releases, as seen below, utilising hyper-realistic textures and shaders.

In order to begin the implementation of this interactive VR tour, various resources will be required. Firstly, the 3D scans and photographs of the cave would need to be acquired from the Museum of Altamira. Following this, a team of programmers familiar with coding VR content, as well as animators and sound engineers would need hiring. All members of the team will be required to have prior experience in the field of VR implementation, in order to make the virtual tour of the cave as fluid, immersive, and realistic as possible. The following is an interactive document displaying prototype images of the virtual reality experience:

https://www.flipsnack.com/mcim1/cave-of-altamira-virtual-reality-experience.html

The real question is what does this VR experience have to offer that existing forms of digital preservation don’t? Firstly, unlike the museum replica, it can be accessed from anywhere or anyone that has a VR headset at their disposal. As a result of this ease of accessibility, it opens the Cave of Altamira up to a more international audience, allowing people on the other side of the world, who might never have had the opportunity to visit this region of Spain, to immerse themselves in an ambient and realistic experience of one of the world’s greatest marvels. VR is such a rapidly growing industry that promoting any sort of awareness of the heritage site through the release of this virtual experience could only benefit the Altamiran community. With more people aware of the cave’s existence, it may encourage people living more locally, such as in Europe, to travel to northern Spain and experience the location for themselves. In fact, as of 2014, five random visitors are selected to enter the cave wearing special suits, masks and shoes. This could potentially further compel people to travel to Altamira, since after experiencing the jaw-dropping digital VR experience, they may want the chance to then see the original cave with their very own eyes. Most importantly however, is that even if users of the VR experience don’t want anything more than to immerse themselves in a breathtaking portion of history, they can do so in a way that is as close to being in the actual cave itself, without causing the paintings within any damage. In reality, the VR experience may even become more compelling the genuine article, seeing as it not only allows the user to travel to this fascinating place, but to also observe it at various points in time, spanning over 36,000 years.