Much has been written about what is considered “the most remote island”, due to its location in the Pacific Ocean. The gigantic volcanic stone statues, known as moai, the still undeciphered writing of the Rongo Rongo symbols, and the history of some inhabitants who were about to disappear, have originated the myth of Easter Island. The island was discovered on Easter Sunday in 1722, and taken over by Chile in 1888. Its fame and World Heritage status arise from the 887 extant stone statues known by the name “moai”, whose creation is attributed to the early Rapa Nui people who inhabited the island around 300 AD. The moai in the park are of varying height from 2 to 20 meters (6 to 65 ft). The volcanic rock formations quarried for sculpting are a distinctive yellow-brown volcanic tuff found only at the Ranu Raraku on the southeast side of the island. Some of the moai were also carved from red scoria. The ceremonial shrines where they are erected for offering worship are known as “ahu”. Of impressive size and form, they are normally built close to the coast and parallel to it.

The Moai

The more than nine hundred known moai sculpted by the ancient Rapa Nui are distributed throughout the island. Most of them were carved in the tuff of the Rano Raraku volcanic cone, where more than four hundred moai remain in different phases of construction. The historical period of the entire development of the various construction techniques lasted between 700 AD and 1600 AD.

Everything indicates that the quarry was suddenly abandoned and statues were left half-carved in the rock. Virtually all of the finished moai, originally located on a ceremonial platform or altar, called ahu in the Rapanui language, were later demolished by the native islanders in the period following the cessation of construction, in the 15th century. Since 1956 a few of them have been restored.

Dennis Jarvis, 2019

Dennis Jarvis, 2019

Dennis Jarvis, 2019

The meaning of the moai is still uncertain. The most common theory is that the statues were carved by the Polynesian inhabitants of the island as representations of deceased ancestors, in such a way that they projected their mana (supernatural power) onto their descendants.

They had to stand on the ahu (ceremonial platforms) with their faces towards the interior of the island (except for the seven located in the Ahu Akivi and a four-handed moai signaling the winter solstice in the Ahu Huri A Urenga) and, after placing eyes on them made of coral with a pupil of obsidian or red volcanic rock, they became aringa ora (‘living face’) of an ancestor – the full name of the statues in the local language is aringa ora or te tupuna (‘living faces of the ancestors’ ). With the restoration of the ahu Nau-Nau on Anakena beach in 1978, it was discovered that coral plates were often placed in the eye sockets as eyes. These were removed, destroyed, buried, or thrown into the sea, where they have also been found. This is consistent with the theory that the villagers themselves toppled them, perhaps during tribal wars.

The first European sailors who, at the beginning of the 18th century, arrived on Easter Island could not believe what they were seeing. In that small area of land, they discovered hundreds of huge statues across the surface of the entire island.

The People: Rapanuis

The Rapanui people descend from the first settlers from Polynesia.

The Rapanui or Pascuenses society was governed by the ariki, with ancestry attributed directly to the gods, and was divided into tribes (mata) with highly stratified classes. Each tribe occupied an area (kāinga). Most of the population lived inland, next to the cultivation areas. On the coast, the religious, political, and ceremonial centers (Anakena, Akahanga) were established where they worshiped the almost deified ancestors represented by the moai.

The first contact of the Easterners with a Westerner took place on April 5, 1722, when the Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeween arrived on the island.

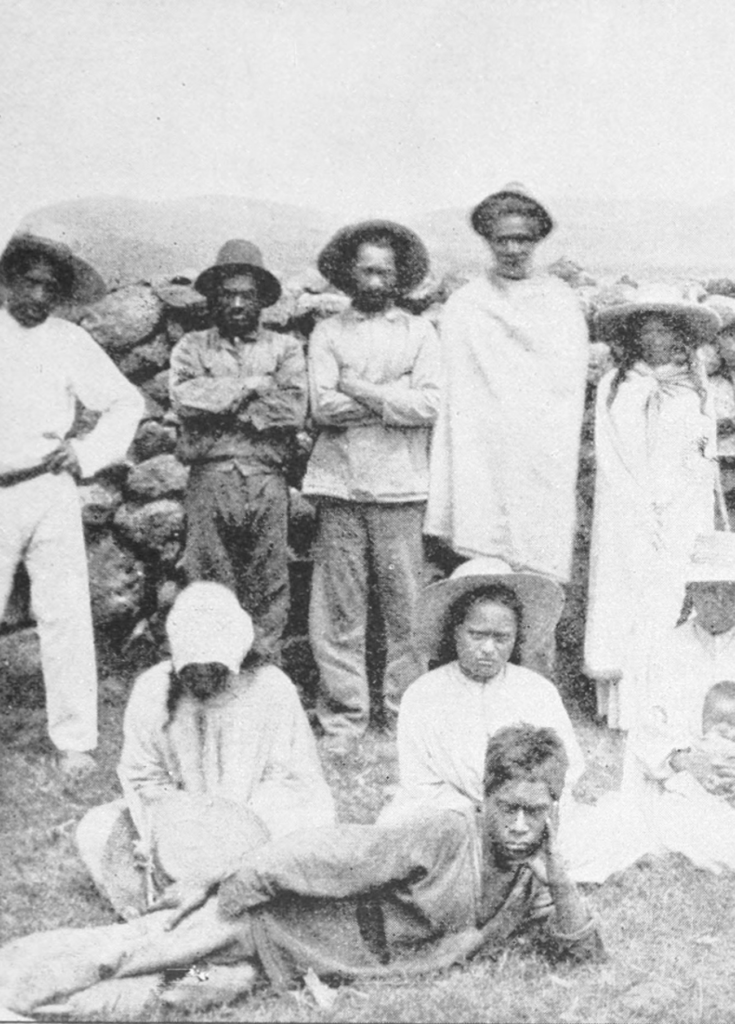

William J. Thomson, 1891

It is estimated that the population of Rapa Nui suffered an overpopulation crisis in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which would have caused wars between the tribes, with the consequent destruction of the ceremonial altars and the abandonment of the quarries in which the moai were carved. . The natives began to live in caves and had to periodically suffer from food shortages. Then a new ceremonial arose: that of the Tangata Manu (‘bird-man’).

The people of Easter have inhabited “Rapa Nui” or “Easter Island” since around the beginning of the 13th century AD. They came to her from other islands of Polynesia. Geographically, the island is part of Oceania, but politically it belongs to Chile (South America). Although it is located at the latitude of Caldera (Atacama region), it depends administratively on the Valparaíso region.

The Food

The typical food of Easter Island is based mainly on marine products. It is well known that a fundamental part of the development of Rapa Nui was based on fishing, and it was from there that many of its great traditions came (including culinary ones) and that they continue to this day.

Along with marine products, the second strong point is in agricultural products. Yes, fruits and vegetables that grow on the island are a fundamental part of the diet of the natives and something typical nowadays.

Finally and a little lower in the order of priorities is the lamb and beef, but it is extra and not the most typical in Rapa Nui.

Fish are and will always be a basic part of Rapa Nui cuisine. Among the most typical and outstanding of the island are tuna, Mahi Mahi, Sierra, and Kana Kana. The most unknown of these 4 are the Mahi Mahi and the Kana Kana. The first is a delicious spineless fish found in all oceans but is strong on the coasts of Easter Island. It can be up to 2 meters long, and its soft white meat makes its flavor a unique dish. The Kana Kana is a fish almost exclusive to the island and that surprises with its white color. Served on a plate it is quite soft and smooth with an incredible taste on the palate.

There are many kinds of seafood, but the most served in Rapa Nui are lobster, shrimp, and Monkfish, exclusive from Easter Island, which is a species of lobster native to the island, but with a much smaller size.

Sweet potatoes, bananas, sugar cane, and pineapples are a typical addition to most preparations and a delicious side and/or dessert. Most of these agricultural products were artificially introduced to Rapa Nui, but today they are part of its culinary tradition.

Mythology

Being an island that today continues to celebrate its ancestors, it is very easy to see how it has its autonomy in terms of the way of understanding the world and the natural phenomena that one has.

They have a very defined and marine-based worldview. This is because most of the adventures, beliefs, and forms of expansion were always linked to the constant trips that their adventurers made.

The ancient Rapa Nui natives were not only in contact with nature for which they had to find an explanation, but also concerned themselves with the origin and creation of man, his way of life, and his survival. This, unlike the study of other mythologies, only happened in the Rapanui mythology.

The First King: Hotu Matu’a

According to what the natives themselves say, the first king of the island and the first person to arrive there was Hotu Matu’a, a colonizer from the Marquesas Islands. The god Make-Make appeared in a dream to the sage Hau-Maka so that the ariki Hotu Matu’a would know that it was his destiny to travel to Easter Island; that is, to Mata ki te Rangi (Eyes that look to Heaven).

First, the ariki would have sent seven explorers to the new land, to recognize what Hau-maka saw. These explorers would have been two sons of Hau-maka: Ira and Raparenga; and five sons of Huatava (Hau-maka’s brother): Ku’u Ku’u, Ringi Ringi, Nonoma, U’ure and Mako’i the island is called “Te pito o te kainga” (Navel or extreme point of the matrix).

There are many stories around Hotu Matu’a, but the one that relates to Akahanga is set in the last days of this legendary character. Oral tradition tells that his last days were spent at the top of the Rano Kau volcano, and after his death, his children took his body and moved it to the Akahanga area. There he was buried under a great stone tower and remained resting for years. The location of the site selected for the location of the tomb of Ariki Henua in the center of the coastline could be justified, because in this way the mana or power that emanated from it, was distributed equally to both sides of the island, giving good harvests, and good fishing for all people. From the previous story, it is also told that a tribe wrapped in the ambition to reach the top of the social ladder, unearthed Hotu Matu’a and stole the skull from him buried, although years later it was recovered by the original descendants of the king.

The Creator: Make-Make

The myth says that after Make-Make had created the Earth, he felt that something was missing. One day he took a gourd that contained water, and with amazement, he realized that when he looked into the water, he saw his face reflected in it. Make-Make saluted his own image as he noted that it featured a beak, wings, and feathers. So it was that while he was looking at his reflection, at that very moment a bird landed on his shoulder. Observing the great similarity between the image of him and the bird, he proceeded to take the reflection of it and united it with that of the bird, thus being born his first-born.

But despite this, Make-Make also thought of creating a being that had the image of him, which would speak and think as he desired. He first fertilized the waters of the sea, and as a result of this, the fish appeared in the waters. But as the result of this was not what was expected, he later proceeded to fertilize a stone in which there was red earth, and from it, the man emerged. Make-Make was very happy to have created man, as the creature that he desired; and as he observed that he looked very lonely, he would later create the woman as well.

A long time later, Make-Make would appear to Hau-Maka in a dream and would indicate and explain how to get to an uninhabited island (Easter Island), so that King Hotu Matu’a would have his new home there. and his people. Later, Make Make with Haua, they would take the birds to the motu (islets) in front of Rano Kau; so that he is worshiped through the annual ceremony of Tangata Manu (the man-bird).

The Bird-Man: Tangata Manu

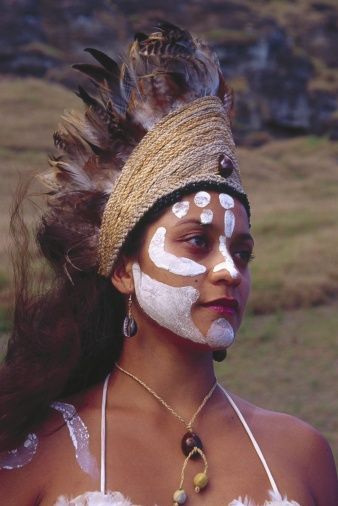

Every year, the representatives of the different Rapanui tribes climbed the Rano Kau volcano to celebrate in the ceremonial center of Orongo, the new competition for the election of the tangata manu, who held the military and political leadership of the island for a year. The contenders were chosen by dream revelation by the Ivi Atua (individuals with the gift of prophecy). Each of the contestants would designate a Hopu Manu, who would swim to Motu Nui and reach the egg; while the contenders waited in Orongo. The joust was very dangerous and many hopu manu died from sharks, drowning, or falls.

Once the hopu manu had presented the egg to the contestant, a fire would be lit on the inland slope of the Rano Kau volcano; the location of the fire would announce to the entire island whether the new tangata manu was from western or eastern clans. The winner received the new name and title Tangata Manu and great power on the island, including that his clan had the unique rights to collect the Motu Nui seabird eggs and chicks from the station. The manu tangata then led a dance down the Rano Kau and continued to Anakena, if it was from western clans, or to Rano Raraku, if it was from eastern clans.

The cult of the bird-man was suppressed by Christian missionaries in the 1860s, with the last ceremony held in 1867. The origin of the cult and its duration is unknown, as is also unknown whether this cult replaced the religion related to the moai or if it coexisted with it, although Katherine Routledge was able to collect the names of 86 tangata manu.

The Music

The music of Rapa Nui can be divided with a timeline marked by the arrival of foreign influence. Between 1870 and 1950 there was a great connection with Tahiti, which resulted in the introduction of Polynesian music and the almost oblivion of their music.

Most of the musical themes of the ancient period, before 1870, were essentially vocal, songs without musical instruments. Most of the aku-aku chants, dedicated to the spirits, were performed with a nasal tonality and rhythmically accompanied by striking two hard stones. There were also polyphonic songs performed by various people and ceremonial songs related to life circumstances, important events, traditions, war, or deaths.

The most important instrument of ancient times was the keho. A hole was made in the ground, about 60 centimeters deep and the same wide. Sand was placed in the bottom and a split gourd was buried to act as a sounding board with a dancer inside of it.